< Athenscope Athens C

Title of the architectural competition project:

Redesign of the Kaisariani Monument as a "Memorial Against

All Forms of State Violence"

Design and Planning: Ioannis Savvidis

Construction: Kyriaki Deutereou

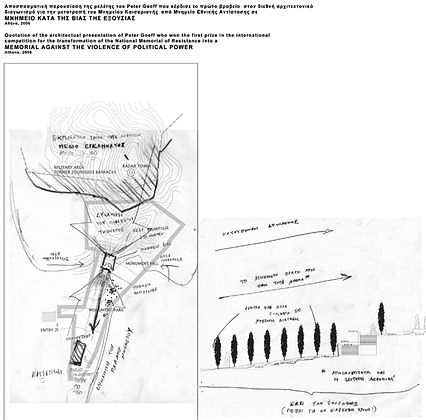

This presentation introduces the winning design for the new monument dedicated to resistance against arbitrary state violence – shown through a white architectural model and the design drawings.

The official name of the existing monument is "Monument to the Heroes of the Resistance". It was intended to emphasize the cross-societal nature of the resistance against the Axis occupiers.

For years, the construction of a central monument commemorating both resistance and national pride

was the subject of fierce debate.

The first drafts, developed around 1956, were rejected because they were heavily influenced by Soviet – and thus Stalinist – architectural and artistic styles. This would have alienated the non-leftist resistance fighters, who had widespread public support.

The late 1950s saw violent street clashes that shook Athens and forced many into exile. The memory of the civil war still weighed heavily on the collective consciousness.

It wasn’t until 1966 that the Association for the Erection of Greek Resistance Monuments reached a unanimous decision: the

monument would be built on the grounds of the Kaisariani shooting range– a site where many resistance fighters had been executed by the German occupiers. Since then, it has been known as the Kaisariani Monument (and colloquially as the "Grave Hand").

However, even during the communist era, crimes against humanity continued – and increased – just 300 meters to the east, in the Laiki Doxa camp on the slopes of Mount Hymettos.

Following the restoration of democracy, the National Council of

Justice launched a competition to redesign the monument.

Impession of Redesign of the Kaisariani Memorial at the show

The goal was to create a memorial for the victims of all forms of arbitrary violence – encompassing both the victims of resistance and the victims of communist repression.

The front of the monument (under heritage protection) is to remain unchanged, while the back – facing the former torture camp – is to be redesigned accordingly. This integrative approach is unprecedented in the history of comparable memorial sites.

How much memory can a monument contain?

Is it possible to commemorate in one and the same place if those responsible are also being honored?

As during the monument’s original construction, considerable resistance is to be expected.

Impressions of

Redesign of the Kaisariani

Memorial at the show

The panel of the architectural competition project